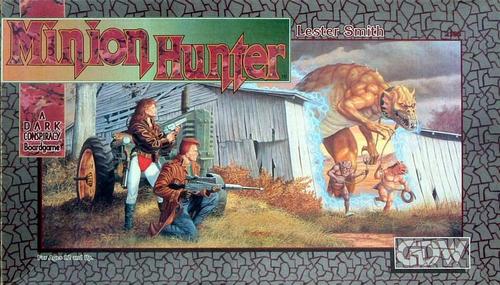

With Game Designers’ Workshop starting life as a boardgaming company, it was probably little surprise that Dark Conspiracy eventually got its own boardgame – Minion Hunter – in 1992. Created by Lester Smith, and developed with both a solo and co-operative style play (for up to six players) in mind, it pits the namesake Minion Hunters against a number of Dark One plots across the breathe and width of Dark America. In a race against time, the players need to upskill, and fit out their characters before it is too late!

So, is the career of a Minion Hunter everything they say it is? Does it lead to a life of wealth and glory, or simply madness and death? More over, are the players themselves going to be able to survive a game that offers as much balance and consistency as a lost marble? Let’s find out!

Now, I know that some people might say that the play style and the game mechanic concepts behind Minion Hunter might be somewhat passé in today’s ‘Eurogame’-centric world, but back in 1992 this type of experience was fresh and new – especially when Talisman was about as complex as boardgames got at the time. Playing it more recently, however, one definitely see its cracks and unbalanced design choices. As such, the reality might be that the best thing about Minion Hunter was the fun you had with your friends and family all those years ago…

However, one can not say that it is a totally unplayable boardgame. Minion Hunter definitely has it good points and, with a bit of work and house rules is quite playable with those not expecting too much from the experience.

The core concept of Minion Hunter is essentially the same as its parent; the roleplaying game Dark Conspiracy. Each player takes on the role of an adventurer (one of the the game’s namesaked ‘Minion Hunters’) as they attempt to stop the nefarious plots of four core Minion Races – the Fey, ETs, Nukids and Morlocks – before it is too late (and one hazards a guess that they bring about the end of the world as humanity knows it). In play, this becomes a race as the players together try to up skill and equip their hunters, while also attempting to stop the various Minion Races plots as the develop.

The Game

Minion Hunter comes in a large box, and includes quite a number of punch out cards, counters and the dice needed for play. The board itself, however is the standout addition to the components, with the largest and most detailed version of Dark America to be found anywhere in the game line printed upon it. Not only is this map actually a core mechanical part of the game (used extensively later on in play when the players are racing to stop one or other of the Minion Races from hitting their plot point win limit), but it also conveys a good idea of just how this America has meant to have changed since the coming of the Greater Depression.

As stated on the back of the box, Minion Hunter comes complete with:

- an 8-page rulebook, complete with game encounter tables

- a full-colour mounted game board with a map of Dark America and tracks for character careers and minion plots

- 72 Plot cards

- 40 Equipment cards

- 10 pawns with full colour stickers

- a tablet (as in pad) of character sheets

- 100 paper money bills (which need to be chopped up)

- one 10-sided die (used for skill tests)

- one 6-sided die

While I won’t be going into a full description of game play1, I would take the time to discuss some of the better aspects of the game, as well as those that really hold it back from being one of those classic boardgames we all know and love.

The Good

When Minion Hunter gets it right, it really gets it right. While it’s not a boardgame that can quickly be completed (a full game taking at least two to three hours from beginning to end), the individual player turns within the game are simple and active, meaning that play fair hums along once everyone understands what they are doing. For younger players, such as my boys, this is an excellent selling point, as they are always engaged in the game and don’t need to wait too long before they get to roll the dice, move their pawn or fight a minion, etc. I have also experimented with alternating the game length by reducing the number of plot cards, but this has meet with varied success, mainly because the losing conditions of the game also rely on these cards (i.e. by reducing the number of plot card randomly one or more of the Minion Races might not have enough points to defeat the players).

When Minion Hunter gets it right, it really gets it right. While it’s not a boardgame that can quickly be completed (a full game taking at least two to three hours from beginning to end), the individual player turns within the game are simple and active, meaning that play fair hums along once everyone understands what they are doing. For younger players, such as my boys, this is an excellent selling point, as they are always engaged in the game and don’t need to wait too long before they get to roll the dice, move their pawn or fight a minion, etc. I have also experimented with alternating the game length by reducing the number of plot cards, but this has meet with varied success, mainly because the losing conditions of the game also rely on these cards (i.e. by reducing the number of plot card randomly one or more of the Minion Races might not have enough points to defeat the players).

The rules of Minion Hunter are also incredibly easy to learn; coming it at just 8 pages they are, for the most part, well written and structured. This combined with the ease of game set up means that you are quickly ready to play (unlike a number of more modern boardgames that seem to longer to prepare than actually complete), and conversely allows you just as quickly pack-up afterwards. While these two aspects might lead one to think that Minion Hunter lacks depth, this a misconception that a number of first time players often have. On the surface the game might look ‘Monopoly-like’ with the players moving around the outside Career track, collecting skill points and equipment, but this is only one half of the game. The other half, which ramps up decision making aspect of play, are the plot mechanics and the Plot Track. With plots rapidly coming to fruition, the players must decide when or if they are going to face one of the developing plots (which will resolve itself with or without the player’s intervention), versus their desire to build up and be better equip their hunter to face future plots. With a few Minion Race plots resolved with out being stopped and the game quickly piles on the pressure as the players can readily see just how close they are to losing the game at all times.

And for a game that really is one of co-operation, the designer made a great decision in adding a neat little competitive element. The simple process of rewarding a hunter by allowing them to keep any plot cards they successfully resolve (each of which has the number of plot points listed on it) adds an edge to the game, pushing the players to often take risks they might not have otherwise done. At the end of a game, it is pleasantly surprising to see the player’s adding up these points, with the one with the highest total being declared the ‘Most Famous’ (which only matters if the good guys win, of course, because, if they lose – to quote the rules – ‘the most famous Minion Hunter will also be the first one hunted down and killed by the Dark Minions‘).

The Bad

But for all the good fun Minion Hunter brings to the kitchen table, it most definitely has some overwhelming flaws. In fact, I’d go far enough to say that these issues have the potential to overshadow any enjoyment and re-playability of the game (especially for adult gamers).

The mechanic that impacts the game play the most in this way is Minion Hunter’s in-game currency system. These rules relying on players drawing random equipment cards (when instructed by spaces on the Career Track or in other places) and deciding whether they will purchase the asset or weapon at the price noted or if they’d rather trade in the card to receive a dollar amount equal to its listed ‘Turn In’ value (usually a percentage of the purchase price). While on its own these don’t seem like bad rules – you can imagine the Minion Hunter passing on a lead for a cut of the profit – the Turn In values listed on some of the items are just game breaking. This is demonstrated no better than with the Jet equipment card; where most equipment has a Turn In value in the tens or hundreds of dollars, the jet has a Turn In of $65,000. In other words, a random draw of a card can instantly give a character enough money to purchase 95% of all the equipment in the game. This is compounded by the fact that the bonuses received by this cards are often considerable, especially early in the game). Worse still the cut-up playbill notes provided in the game don’t match the denominations required, and in most games you end up needing to record your bank balance somewhere on your character sheet.

The money mechanic rears its ugly head again on the Career track (the spaces around the perimeter of the board that provide opportunities to gain skills and equipment cards). In one space it gives a character the chance to win 50 thousand dollars, with a single die roll, a success allowing them access to a destabilising amount of money. This is equally a good example of the second big issue I have with the game, the balance of encounters on the Career track. As with the example noted, the benefits gained are punishments doled out when landing on particular spaces (events) on the track are often unbalanced. Further, there are plenty of spaces on this track that have nothing but bad outcomes or force the character to waste their turn as they have to move to a Minion Plot location even if they are incapable to resolving it. This can quickly lead to some characters building up numerous skill points while others are randomly forced out to spend valuable actions on the Map section or in Hospital (often the outcome for failing a test on a Career space).

These are all symptoms, in my opinion, of a unevenly balanced game. While some of the flaws I’ve described could be neutralised through house rules I’m not sure that the overwhelming issue of balance could ever be corrected. This plays out, more than anywhere else, in the pacing of the game. At the beginning, the fledgling Minion Hunters will find it nearly impossible to successfully complete any Career Track events successfully, and Plot Track cards will rapidly resolve as the players are unable to deal with them. By the end of the game, however, this is totally flipped on its head, with all the challenge gone from any Career space, and the characters easily able to flit from one plot card location to the next defeating the Minion Races and random encounters with ease. These two elements emphasis the frustration that some players have with Minion Hunter, and has resulted in more than one game begin abandoned due to annoyance or the realisation that victory had become inevitable even with a stack of plot cards yet to play out. This is not to say that there isn’t a sweet spot around the mid-point of the game, but it never long enough to really deliver.

These are all symptoms, in my opinion, of a unevenly balanced game. While some of the flaws I’ve described could be neutralised through house rules I’m not sure that the overwhelming issue of balance could ever be corrected. This plays out, more than anywhere else, in the pacing of the game. At the beginning, the fledgling Minion Hunters will find it nearly impossible to successfully complete any Career Track events successfully, and Plot Track cards will rapidly resolve as the players are unable to deal with them. By the end of the game, however, this is totally flipped on its head, with all the challenge gone from any Career space, and the characters easily able to flit from one plot card location to the next defeating the Minion Races and random encounters with ease. These two elements emphasis the frustration that some players have with Minion Hunter, and has resulted in more than one game begin abandoned due to annoyance or the realisation that victory had become inevitable even with a stack of plot cards yet to play out. This is not to say that there isn’t a sweet spot around the mid-point of the game, but it never long enough to really deliver.

Trivia

Despite being a game that could of, and perhaps should of, been much better, there is a lot interesting information surrounding Minion Hunter. First there is an insight the origin of the game by Dave Nilsen (GDW’s Head of Design from 1991 to the company’s closure). Please note that this quote was direct sourced the Minion Hunter entry on Wayne’s Books’ Dark Conspiracy page (the best place to source old physical copies of DC supplements).

This game was actually deliberately made to use the game boards we had in stock. GDW at one point was intending to go into more high-end board games, like a Star Vikings game with plastic pieces, and our print buyer found a great deal on these mounted hard game boards, so we had about 10,000 in our warehouse, and this game was meant to use them. It was a great little game. Actually, the cooperative component of the game came out of our in-house playtesting, and was not originally in there. It just came so naturally to us to want to cooperate to defeat the minions, that we got Les to add that in. I have played it a number of times with non-gamers in the years since GDW, and everyone loves it. I was a guest at a Con in Salt Lake City in ’94 along with a couple guys from White Wolf, and we spent a lot of the weekend playing MH. They loved it. The only real problem with the game is the paper money. It’s a pain to cut up, and comes in the wrong denominations. I usually just keep track of the money with piece of paper and pencil and keep the money “mint.” We never did make a second boardgame, although I really would have liked to do a MH expansion based on the “Proto-Dimensions Sourcebook” we put out, which would have been a natural. So when we went down there were still 5000 unused boards in the warehouse.

– Quote from David Nilsen (6/10/2012)

There was also a supplement created for Minion Hunter, called Minion Nation – the Minion Hunter Expansion Kit, which added 16 new equipment cards (the majority being translations from the DarkTek Sourcebook), expanded encounter tables (allowing for more bad stuff to happen to your Minion Hunters), and a glossary of Dark Conspiracy terms (for those who had obviously come to the setting through the boardgame rather than the RPG). While it really isn’t worth the then $4.50 for the folio cardstock cover and 8 pages of additional rules, it does give players options for random plots as well as variants for playing the game with a darker or friendly game mechanics.

Probably the most interesting bit of trivia arising from Minion Hunter, however, is what it grew into. Back in the mid-90s, bulletin boards and simple multiplayer online games were growing in popularity, and it seemed natural that boardgames should also move into the digital sphere. Around this time Key West-based MPG-Net (best known for its Kingdoms of Drakkar RPG), licensed the rights to Minion Hunter. The result was an online version of the boardgame, that had some following at the time. Of course, right when online companies like MPG-Net were growing, GDW, a traditional pen and paper publisher was recognising the end was near. Instead of cutting and running, Frank and management of GDW closed up shop in an organised manner, making the best of the properties in their stable. As we know Frank kept his favourites (such as Space 1889), while others from GDW got control back of their own games (such as Marc Miller and Traveller). For Dark Conspiracy, however, there was no strong supporter (Lester having moved on by that point), and besides MPG-Net seemed willing to purchase the rights to the setting. And so it was Dark Conspiracy ended up with MPG-Net and its CEO James Hettinger. When the sun finally set on games like Minion Hunter Online, James retained the rights and its been his willingness to license them that has allowed a number of people the opportunity to keep the game alive.

Thoughts

I really, really want to love Minion Hunter, but unfortunately beyond being a fun alternate to simple games like Dungeon or Risk to play with my kids, it really doesn’t have the depth to match more modern boardgames. This isn’t helped by the broken money mechanics nor the unbalanced nature of its core rules. However, one can not but imagine what it might look like if it was republished today by one of the big boardgame publishers (such as Fantasy Flight Games did with Arkham Horror). I know that the rough edges would have been filed away, and a lot of what is provided through the character sheets or the encounter tables would be replaced by tokens and cards respectively. But, would it still be a game I could to play with my two boys? I think the answer there might be no…

And maybe that’s what Minion Hunter’s legacy should be… family fun as Dad trips through his youthful nostalgia… nothing more and nothing less.

Design: Lester Smith

Development: Loren Wiseman

Editing & Typesetting: Stephen Olle

Art Direction: Amy Doubet

Graphic Design & Production: Steve Bryant, LaMont Fullerton & Kirk Wescom

Proofreading: Steve Maggi

Playtesting: Nick Atlas, Steve Bryant, Anthony Cellini, Frank Chadwick, J. E. Cotton, J. L. Cotton, Jason Huls, Pat Lowery, Steve Maggi, Dave Nilsen, Stephen Olle, Christine I Smith, J. A. Smith, Katheryn Smith, Phil Tobin & Greg Whalen

Blind Testing: Ted Carlock, John Hacker, Scott Hutson, John Langford, Stephen M. Taylor, & Ron Thrasher

Illustrations: Janet Aulisio, Liz Danforth, Dell Harris, Rick Harris, Dave Martin & Thomas Darrell Midgette

- This I might do in a future article, if there is any interest. ↩